Unlimited

Fireside Vespers, Week Three

Reading:

Deborah, a prophet-woman, wife of Lappidoth,

she it was who judged Israel at that time. And she would sit under the Palm of

Deborah between Ramah and Bethel in the high country of Ephraim, and the

Israelites would come up to her for judgment.

And she sent and called to Barak son of

Abinoam from Kedesh-Naphtali and said to him, “Has not the Lord God of Israel

charged you: ‘Go, and draw around you on Mount Tabor and take with you ten

thousand men from the Naphtalites and the Zebulunites. And I shall draw down to

you, at the Kishon Wadi, Sisera, the commander of Jabin’s army, and his

chariots and his force, and I shall give him into your hand.’?”

And Barak said to her, “If you go with me, I will go, and if you do not go with me, I will not go.” And she said, “I will certainly go with you, but it will not be your glory on the way that you are going, for in the hand of a woman the Lord will deliver Sisera.”

And Barak said to her, “If you go with me, I will go, and if you do not go with me, I will not go.” And she said, “I will certainly go with you, but it will not be your glory on the way that you are going, for in the hand of a woman the Lord will deliver Sisera.”

Homily:

My wife puts up with a lot. Myself, for starters, and of

course our children. But she also takes a lot of flak as a female pastor that I

as a male pastor simply do not have to deal with. And it isn’t fair that she

has to handle that. But she does and does it well.

There are those who think that because she is a woman she

should not and cannot be a cleric. There are those who would ignore her, talk

down to her, or simply talk over her because they do not recognize her

authority, her office, or her expertise. It is against Scripture, they claim, against

the very Word of God, to have a woman speak out in a Church, let alone have a

woman serve as pastor, priest, or bishop. It has always been men, and exclusively men, who serve at

the Altar. No one spoke of ordaining women until the 1970s. Can two millennia

of Church tradition and practice be wrong?

Both sides have their go-to texts, of course: those that seem to exclude women from the service of God against those that explicitly speak of women as deacons and apostles. One can fence with Scripture all the live long day, should one be so inclined and lean a bit toward masochism.

Both sides have their go-to texts, of course: those that seem to exclude women from the service of God against those that explicitly speak of women as deacons and apostles. One can fence with Scripture all the live long day, should one be so inclined and lean a bit toward masochism.

I cannot and indeed ought not speak for women clergy. They

are quite capable of speaking for themselves, as their ministries clearly

demonstrate. And a recent spate of scholarship argues strongly that such women

are not alone. We have evidence—increasingly powerful evidence, in my judgment—that women

served openly as deacons, priests, and bishops in the early Church and into the

early Middle Ages.

It wasn’t until the eleventh century that the very meaning of ordination was transformed into an exclusively celibate male cult via sweeping churchwide reforms. That so many medieval bishops wrote so many

letters condemning women serving at the Altar is a rather strong indication that

women regularly served at the Altar. And the research into this is neither

liberal nor fringe, mind you, but published by scholars of the Roman Catholic

Church. I could recommend some books, if you would like.

We are always so certain of what it is God can and cannot

do, the clear reading of Scripture, the unbroken witness of tradition—only to

discover how blinkered and blinded we often are in our surety. The whole story

of the Church, and indeed of Israel before it, is that of in-groups being

shocked by those foreigners, sinners, and unworthies upon whom God chooses to

pour forth His Spirit and His blessing.

When Jesus, having made something of a name for Himself in

the Galilee, returns home to Nazareth to preach a sermon in the synagogue, it

isn’t His bold proclamation that He is the Messiah come to declare the Lord’s

Jubilee that upsets them. The Nazarenes love that; it’s the fulfillment of

their hopes and dreams. A local boy made good! But then Jesus announces that

God’s will and work are not limited to Israel, let alone to the remnant branch

of David’s line. And that’s what shocks them. That’s what enrages them—to the

point that they try to throw Him off a cliff.

Tell us that the Messiah has come to us, and we rejoice.

Tell us that the Messiah has come to those outside the circle—to those who

ought to stay in their proper place—and suddenly we turn from joyful crowd to

foaming mob. It’s always been this way. Genesis champions the younger brother

over the heir, Exodus the slave over the master. When the Law of Moses

specifically excludes Moabites from the community of Israel, the Book of Ruth in

response uplifts a woman of Moab as the ideal Israelite and great-grandmother

to the king.

With the advent of the Church, questions of identity, of who

can or cannot be a Christian, came to the fore. The great query wrestled by the

Apostles was the inclusion, not of women, but of Gentiles. Could one become a

Christian without first being a Jew? What about Ethiopians, Samaritans, Greeks,

Romans? Surely not they, Lord. Yet everywhere we sought to draw the line, God

emphatically stamped it out. And each time we’re shocked.

It continues to this day. The Vikings, once the scourge of

Christendom, settled down to become the Nordic Lutherans of today. The Muslim

refugees we feared might Islamicize Europe are instead filling up her empty

churches. Our enemies are rarely the people outside the community of the

Church, but those within, our brothers and sisters, our very selves.

Muslims aren’t stealing children away from Sunday worship;

our own apathy and acedia have done that. Pagans didn’t cause the clergy sex

scandals rocking the Catholic Church. We did that. We, as Christians, building

our little walls, forming our little tribes, are our own worst enemies. That

may well be why Christ chose us for His Body, to be His hands and feet in the

world: because we’re the ones who are broken, fallen, sinful, small. We’re the

least likely and the least liked. We’re sinners in the hands of a loving God. And

if He can work through us, heck, He can work through anybody.

My point is simply this: no one owns God. No one can place

limits on His power, His mercy, His action, His love. He is constantly

surprising us, constantly toppling our temples, constantly making all things

new. And that means that we have to die daily to our assumptions and our

prejudices and the false idols we so love to fashion in our own hearts. Because

Christ is doing the same thing today that He’s always done and always will: He

is drowning us in our sins, raising us to new life, and calling every wayward

sinner home in Him.

As soon as we think that God cannot work in any given way through

a certain sort of person—that’s exactly when God will do just that. And woe be unto

us when we stand in stubborn opposition to the will and the work of the Lord God

Almighty.

In Jesus. Amen.

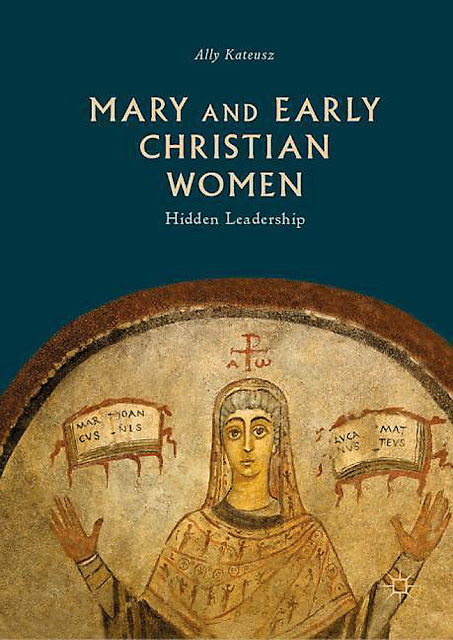

Mary and Early Christian Women: Hidden Leadership

by Ally Kateusz

Crispina and Her Sisters: Women in Authority in Early Christianity

by Christine Schenk, C.S.J.

The Hidden History of Women's Ordination: Female Clergy in the Medieval West

by Gary Macy, S.J.

Ivory Vikings

by Nancy Marie Brown

The Cruel Eleventh-Century Imposition of Western Clerical Celibacy

by Joe Holland

Comments

Post a Comment