Our Father

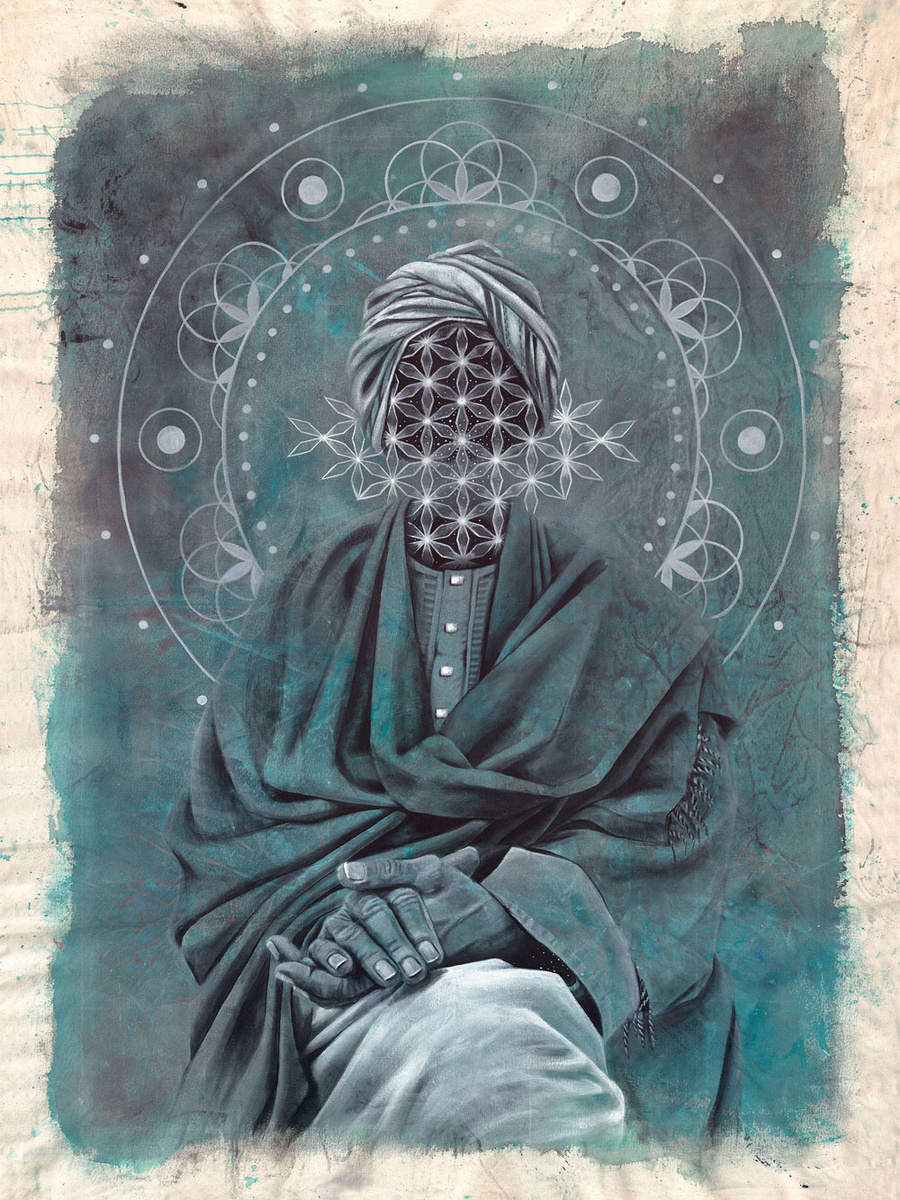

Nirguna Brahman, by Miles Toland

Lenten Vespers, Week One: God the Father

A Reflection on God and the Gods, by David Bentley Hart:

It is possible to mistake the word “God” for the name of some discrete object that might or might not be found within the fold of nature, if one just happens to be more or less ignorant of the entire history of theistic belief. But, really, the distinction between “God”—meaning the one God who is the transcendent source of all things—and any particular “god”—meaning one or another of a plurality of divine beings who inhabit the cosmos—is one that, in Western tradition, goes back at least as far as Xenophanes.

And it is a distinction not merely in numbering, between monotheism and polytheism, as though the issue were simply how many “divine entities” one thinks there are; rather, it is a distinction between two qualitatively incommensurable kinds of reality, belonging to two wholly disparate conceptual orders. In the words of the great Swami Prabhavananda, only the one transcendent God is “the uncreated”: “Gods, though supernatural, belong … among the creatures. Like the Christian angels, they are much nearer to man than to God.”

This should not be a particularly difficult distinction to grasp, truth be told. To speak of “God” properly—in a way, that is, consonant with the teachings of orthodox Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Sikhism, Vedantic and Bhaktic Hinduism, Bahá’í, much of antique paganism, and so forth—is to speak of the one infinite ground of all that is: eternal, omniscient, omnipotent, omnipresent, uncreated, uncaused, perfectly transcendent of all things and for that very reason absolutely immanent to all things.

God so understood is neither some particular thing posed over against the created universe, in addition to it, nor is he the universe itself. He is not a being, at least not in the way that a tree, a clock, or a god is; he is not one more object in the inventory of things that are. He is the infinite wellspring of all that is, in whom all things live and move and have their being. He may be said to be “beyond being,” if by “being” one means the totality of finite things, but also may be called “being itself,” in that he is the inexhaustible source of all reality, the absolute upon which the contingent is always utterly dependent, the unity underlying all things …

Obviously, then, it is the transcendent God in whom it is ultimately meaningful not to believe. The possibility of gods or spirits or angels or demons, and so on, is all very interesting to contemplate, but remains a question not of metaphysics but only of the taxonomy of nature … [while] the question of God, thus understood, is one that is ineradicably present in the mystery of existence itself, or of consciousness, or of truth, goodness, and beauty.

Here ends the reading.

Homily:

Lord, we pray for the preacher, for you know his sins are great.

Grace, mercy, and peace to you from God our Father and from our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ. Amen.

We believe in one God, the Father, the Almighty, maker of heaven and earth, of all that is, seen and unseen.

When people say they don’t believe in God, I almost have to laugh; because truthfully the god in whom they don’t believe, I don’t believe in either. Someone claims that God does not exist, and what can I do but agree? God does not exist, not in the way that you or I do.

Rather, God is existence itself, being itself, reality in the fullest, deepest, truest sense. And you and I and everything only exist insofar as we exist in Him. The question of belief in God at that point just sounds silly. For who can doubt existence?

This confuses and frustrates people. The unchurched imagine God to be a fairy in the sky, an old man on a cloud, a magical being whose significance rivals leprechauns and unicorns. When instead I speak of God as the source and ground of all being, they then accuse me of moving the goalposts, of changing the meaning of words. Yet this distinction between gods as spirits within nature, and One God as the Father of us all, predates even Plato, stretching back to well over two and a half millennia.

Moreover, this is the understanding of God on which all of us agree: pagans, Hindus, Christians, Jews, Muslims, and even, I would argue, certain stripes of Buddhists. People who reject this simply have not done their homework, like that one cocky kid who seeks to lead the class discussion when he clearly never cracked a book.

If goodness and beauty and truth are real, if consciousness, being, and bliss are real—and no-one but a madman doubts they are—then this leads us inevitably to the question of God, the question of ultimately reality. What is real, what is true, what is good, that is God. The objection might arise that if we’re speaking of reality, then why bother with the god-talk. That just confuses things. Let us speak instead of physics, of natural laws.

Yet this misses the mark on several counts. We possess a number of logical poofs, as potent today as they were to the ancient philosophers, demonstrating that that which is contingent must rely on something that exists necessarily, that the finite depends on the infinite, the temporal upon the eternal. God thus exists, as it were, logically. And moreover, without Him our logic falls apart.

Of course, while such things prove useful for overcoming the flawed arguments of cynics, what really points us to God is intuition, lived human experience, which all of us share and none can deny. We all crave meaning and purpose and value. We all strive for the infinite horizon, the eternal, the transcendent. We all live not by bread alone but by goodness and beauty and truth. And all of these things stretch beyond the merely material.

Consciousness, being, and bliss are fundamental spiritual realities, which we cannot explain away, no matter how blithely some attempt to fob them off as epiphenomena. There is more to being human than chemistry and physics. The sheer wonder that motivates and undergirds all science, all justice, all art, is itself our reaching out for the divine. We cannot shake the conviction that there is something more, there’s someone there, and we are not alone.

God is not some proposition; God is an experience. And the fact that the overwhelming majority of humanity throughout the overwhelming majority of history has said in chorus, “Yes, we’ve seen Him too,” is proof to us that we are not insane. There is no irreligious species of humanity. Those who would claim otherwise are sadly in denial, because I promise you: everybody worships something. And if your god is not the Creator, under whatever name, then your god is false and it will fail you at the last.

When we speak of God as Father, this is what we mean. Not a sky fairy. Not an old man on a cloud. But the infinite, eternal Source of all, in whom we all live and move and have our being. The Father is beyond all our imaginings. The Father is beyond all limitations. No matter how well we think of God, the Father is always better, always greater, always more.

Can we think of God the Father as a person? Well, certainly not, if by “person” we imagine some limited psychological subjectivity, someone with moods and choices and flaws, who changes His almighty mind, with the fickleness of Zeus. Yet if instead we mean by “person” love, understanding, awareness, freedom, life, bliss, and joy, then God is far more a person than we could ever hope to be.

In truth, God is neither personal nor impersonal but transpersonal, beyond any division we could make between the two. And this makes sense, if again we consider that God is ultimate reality, in whom and by whom all things exist, including ourselves. Clearly, reality as we know it has to be at least as personal as we are, since we are part of it, while also including both things below and forces above our understanding. And ours is but one of innumerable worlds our Father has made.

God transcends all reality. God is always more.

Any theological tradition worth its salt distinguishes between Nirguna Brahman, “God without characteristics,” and Saguna Brahman, “God with characteristics.” The former is God as the absolute transcendent divine beyond all mortal ken; while the latter is God as we can know Him, the immanent divine, closer to you than your jugular. In the words of Martin Luther: “The Father is too high, but the Father has said: I will give you a way to come to me—that is Christ. Go, believe, and embrace Christ.”

Next week we will speak of God the Son. For tonight let it be sufficient to stand in wonder at God our Father, Creator of us all, in whom we all live and move and have our being; without whom nothing at all could exist, nothing could ever be real. We all come from Him, abide in Him, and return to Him. He is the ocean in which we swim, the womb in which we grow, the mind in which we are but thoughts. He is Love itself, Goodness and Beauty and Truth itself, infinite Consciousness, Being, and Bliss.

Whatever we can think of Him, the Father’s always more. More wonder. More life. More joy. If we cannot seem to know Him, it’s not because He’s hidden. The Father simply shines with glory brighter than the sun, and we stand in wordless awe as we are blinded by His light.

In the Name of the Father and of the +Son and of the Holy Spirit. Amen.

If you would like to contribute to St Peter’s ministry online, you may do so here, and we would thank God for your generosity.

Comments

Post a Comment