Copper, Christ, and Cuneiform

Propers: The Fifth Sunday after Epiphany, AD 2022 C

Homily:

Lord, we pray for the preacher, for You know his sins are great.

Grace, mercy and peace to you from God our Father and from our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ. Amen.

Do you ever feel as though you’re shouting into the void? As though all of your efforts, all your good intentions, amount to little more than fistfuls of dust dispersed by the winds? What difference does it all make, really? What good can we do? We cast our nets and cast our nets, all the day and through the night, only to bring them in empty, time and time again. All our efforts have come to naught.

And yet, just one more time, says Jesus. Cast your nets but one more time and see what you might catch. Well, what the heck? Why not?

Some 3,770 years ago, a merchant named Ea-nasir lived in the ancient Sumerian city of Ur. And when I say ancient, I mean that on a scale so brobdingnagian that most of us would have trouble fitting our minds around it. Abraham is said to have lived in Ur more than 4,000 years ago, and in his time that city was already more than 4,000 years old. That’s significantly older than history. We’ve only been writing things down for five-and-a-half thousand years.

Now it seems that Ea-nasir had sold some copper to a customer named Nanni, and Nanni wasn’t happy. He had paid up front for copper ingots that proved upon arrival to be of substandard grade. This was not what they’d agreed on. Nor, it seems, was this the first time that he’d had trouble with such a delivery. And to top it all off, his servant had been treated badly. Lousy customer service. So Nanni did what most of us would do today: he wrote a letter of complaint. Terrible review. One star.

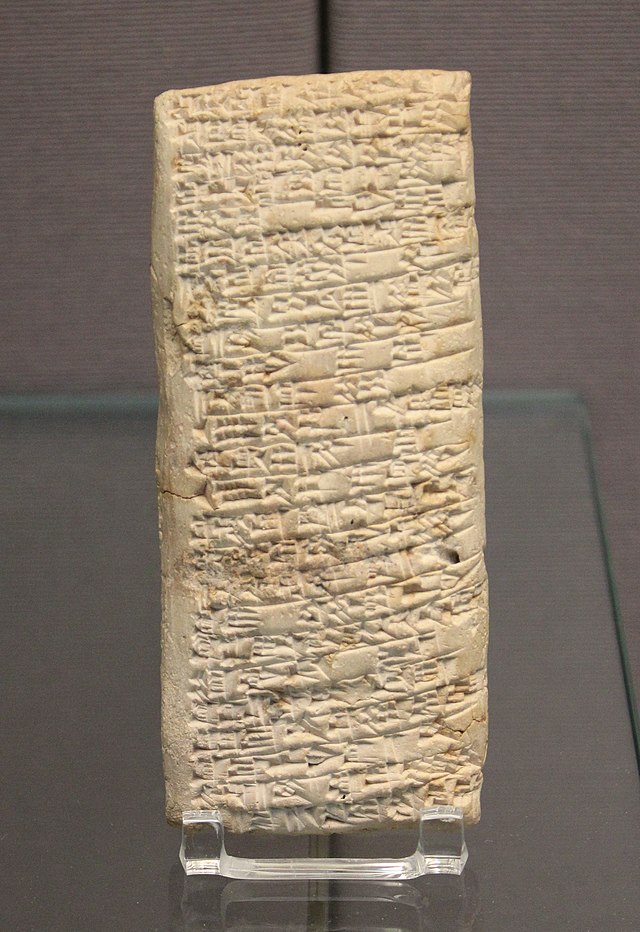

But this all happened before the invention of paper, parchment, or papyrus. Nanni had to write his letter on a clay tablet, with a cut reed, in Akkadian cuneiform. Cuneiform, mind you, is a system of writing older than alphabets, older than Egyptian hieroglyphs. It looks like bird feet in mud. And having thus vented his spleen, Nanni baked this clay complaint and sent it off to Ur in order to give Ea-nasir a piece of his mind.

Here’s my point. There is no more city of Ur. It was abandoned centuries before Christ. Its patron deity is no longer worshipped. The various cultures and peoples who lived there over centuries have long since succumbed to the sands of time.

There is no more Sumeria, no more Akkadia, no more cuneiform. And yet! Sitting on a shelf in the British Museum under a protective layer of glass, densely written and strongly worded, one can still read the Complaint Tablet of Ea-nasir—history’s oldest known written complaint. Now who could have predicted that?

Imagine if 4,000 years from now you were famous in academic circles for a negative review that you posted up on Amazon. I kid you not: in the Year of Our Lord 2022, I regularly see online memes joking about the cruddy copper of Ea-nasir. And granted, that’s pretty nerdy; but just imagine going back in time and attempting to explain all of this to him, why any of us even know his name.

We really have no concept of what impact our actions, our lives will have on generations yet unborn. Everyone accepts the trope in movies that if we were to change even one tiny thing in the past, it would have enormous repercussions for our present. Why then do we have a hard time believing that even the smallest actions in our present will have an outsized impact upon everyone’s future?

The Bible understands this. The Bible has this concept, maybe because the biblical authors were used to thinking of history in terms of millennia. One life, one person, can benefit every generation thereafter—but they won’t be here see it. Abraham and Sarah were promised more descendants than there are stars in the sky; they had one kid together, and he almost got sacrificed. Yet Abraham, we are told, never once doubted the destiny that God intended for us through him. That’s faith.

The teachings of Jesus—and those of the early Church, found in documents like the Didache—place a great deal of emphasis on small sins. And modern people often wonder why. Is it true that insulting someone is really as bad as murder, or that looking upon someone in lust is equatable with adultery? Well, no, not really. Not immediately. But big things have small starts. And that includes big sins. One does not typically turn to the Dark Side on a dime. Evil is a series of contingencies, a number of successive steps leading up to true atrocity.

“He who is faithful in a very little,” says Jesus, “is faithful also in much.” But why is that? Well, for two reasons. First, because virtue must be trained. You practice with small weights before you can lift large ones, yes? The same goes for morality. You work your way up. If you’ve practiced doing what you know to be right, in little ways on a daily basis, then you’ll be the better prepared for when it really counts. In crisis you’ll know what to do.

But the second reason is that little things aren’t actually all that little. Everything in our world, in our lives, is interconnected, interdependent. Autonomy is largely illusory. Everything we do affects others, affects the whole world around us. And it may not seem that way. But our choices are like pebbles that we toss into a lake. They may not appear to do much, but their ripples will reach the farthest shore.

Any tiny kindness, any act of grace or generosity, surely plants a seed. And that seed might not even sprout for generations down the line. It could be that 500 years from now a great artist or prophet or philosopher shall arise because you today were a good parent, a good teacher, a good musician, a good neighbor, or even just a sinner who knew when to ask forgiveness.

Empires will fall. Statues will crumble. Gods will be forgotten. “My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings; Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!” Yet love will bear its fruit in due season. The Word of God never does return empty.

We read from the Prophet Isaiah this morning. There’s a tradition that Isaiah only ever converted one person in all of his ministry, and that his career ended when he got sawn in half whilst hiding in a tree. Not exactly a banner vocation. And yet look at him today. The Book of Isaiah has proven so influential in preparing us for the Messiah that Christians often call it the Fifth Gospel. We read it every Christmas, and all throughout the year.

Or look at Peter in our Gospel this morning. He’s a fisherman who can’t catch fish. All night, casting nets. All night, coming up empty. We know how that goes. Yet Jesus says: one more time. Cast the nets but one more time, out there in the deep. And Peter says, “All right. If you say so. I don’t know what good it’s going to do, but I will do it as you ask.” And of course when he does, they don’t just catch a few fish—they catch a ridiculous superabundance of fish, so many that the nets break.

And that’s when Peter realizes, “Oh. There is so much more going on here than fishing.” And like Isaiah, he cowers and says, “Go away from me, Lord, for I am a sinful man!” These results are not my own; this is surely the work of a higher power. And Jesus says to Peter and the rest, “Do not be afraid; from now on you will be catching people.” It seems that all you have to do, in order to follow God, is be forgiven.

I’m not going to stand up here and tell you that if you just keep at it, then one day, boom, you’ll pull in a miracle. I am not some prosperity preacher who promises worldly reward in this life. I can’t say it won’t happen, of course. But that’s not the point. Do the will of God without expecting clear results. Live a life suffused in prayer, charity, honesty, forgiveness, generosity, and grace. When you stumble, when you fail, when you fall—get up again. Return to the Font of forgiveness. And go back out.

“Duty is ours,” wrote John Quincy Adams; “results are God’s.” I used to think that meant that the immediate failure or success of any endeavor should be chalked up to divine intervention. I don’t anymore. Rather, we are to obey our Lord, period. We are to do as He commands, to forgive as He forgives, to love as He loves us. And we are to do this without thought of reward or of results. Just as we reap where others have planted, so we are planting what others will reap. And God gives the growth.

Blessed are the old who plant trees, knowing they shall not live to sit in the shade. Live like this, my friends, and you’ll never have to worry about earning Heaven, for Heaven shall come to dwell with you while still upon this earth.

Someday, at the end of it all—when the tapestry of Creation is at long last complete, and the Son hands the Kingdom over to the Father, that God at the last shall be all in all—then and only then shall we see how the thread and color of each of our lives has contributed to the glory of the greater design.

Cast your nets. Love your neighbor. Do the good that’s set before you. Ever rejoice that Christ is with you. And He Himself shall bring all things into their truest fruition.

In the Name of the Father and of the +Son and of the Holy Spirit. Amen.

Comments

Post a Comment