Magi Midrash

Propers: The Epiphany

of Our Lord, AD 2021 B

Homily:

Lord, we pray for the preacher, for You know his sins are great.

Grace, mercy and peace to you from God our Father and from our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ. Amen.

Epiphany commemorates the Magi—wise men from the East—who came to Bethlehem, following a mysterious light in the heavens, in order to worship the Christchild, and to offer to Him their famous gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh. We have precious few details as to who these people were or whence they came. Yet in spite of this—perhaps because of this—they have captured the imagination of the Church for thousands of years in ways that few other characters ever have.

Scholars often wonder if the Magi came at all, for indeed only Matthew seems to mention them. Nevertheless there’s little doubt regarding their authenticity from the earliest days of the Church, and their importance reaches beyond mere history. We don’t know that they were kings; we don’t know that there were three of them. An alternate tradition puts their number at about a dozen. Nor do we know their country of origin, though Arabia, Mesopotamia, and Persia are all likely suspects.

What we do know is that they were stargazers; they were Gentiles, not Jewish; and they understood that the Christ had been born in Israel as King and God and Sacrifice. This is not as far-fetched as one might suppose, for indeed prophecies of the Messiah were well-known not only amongst Israel’s neighbors but even to the ancient Sibyls of Rome. The promised Savior had long been expected at this time and in this place.

Beyond this we have precious little information, which has left plenty of room for imagination and legend. Judaism practices a fascinating form of biblical interpretation known as midrash, in which one pays close attention to tiny details and to silences in the text—using sanctified imagination to read between the lines. This results in new stories with new perspectives told alongside the narrative text. Let’s say there’s a character who’s barely mentioned in the Hebrew Bible. A midrash might imagine her story, her reactions, her experience of the events described, not replacing the original story of Scripture but expanding upon it.

One might think of it as fan fiction, but that’s too glib a term to be appropriate. Rather, midrash is a way of inhabiting the Bible, engaging with Scripture, imagining ourselves, or people like us, within the sacred story. In midrash, our stories become part of The Story. I would argue that there are many examples of Christian midrash, legends expanding upon the silences of the New Testament. In the Gospels, for example, we know precious little about Jesus’ childhood. In many ways it’s a blank slate.

But people want to know what happened in these silent years of Jesus’ life. And so we have Christians writing Infancy Gospels, tall tales of Jesus’ formative years, which expand upon and fill in the gaps within sacred Scripture. They are not given the same authority as the canonical texts, but then they were never intended to be Scriptures themselves. They’re midrashim, interpretations, stories.

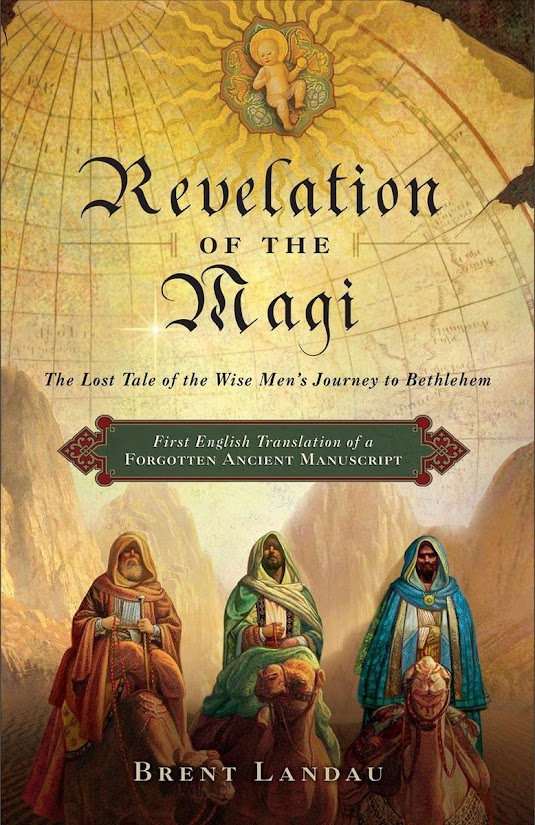

Thus it should come as no surprise that we have a midrash about the Magi—indeed, a very early one, from the third century or so, written in Syriac, which is as close as you’re going get to the language Jesus spoke. The story is called the Revelation of the Magi, and boy is it eager to fill in those gaps. In this midrash, the Magi live in a country called Shir on the far eastern edge of the world, out by the ocean.

In Shir they live on a mountain, which contains a cave, which in turn contains a book of sacred mysteries passed down from Adam in the Garden to his third son Seth, and thus to Seth’s descendants thereafter. Twelve of these descendants, the Magi, are tasked with awaiting a great Star, which had shown in Eden before Adam’s Fall, and as each one of these twelve dies, his office is passed down to a son or male relative.

Then one day, at long last, the prophesied Star appears—a Star far outshining the sun, yet which only the Magi can perceive—and this Star is revealed to them as the Son of God, who is God come into our world and who is everywhere present. At the same moment the Star is speaking to the Magi, He is also being born in Bethlehem, and is present in fact throughout this world and all worlds. The Star leads the Magi miraculously to Bethlehem, leveling mountains as the prophets foretold and replenishing their food as God once fed Israel in the wilderness.

Afterwards the dozen Magi return home, just as miraculously, and when people taste the heavenly bread they provide—an allusion, perhaps, to the Eucharist—all are given different visions of the Son of God, who is revealed fully in the Incarnation of Jesus Christ our Lord, yet who is present in a veiled way within all religions. And this is very interesting, because it changes our understanding of mission. Christians are sent out, in this midrash at least, not to bring peoples knowledge of a Son of God they do not know, but to reveal how the Son of God has already made Himself known to them in their own lands, in their own religions.

There is one Son of God, known fully in Jesus Christ. But wherever the Christian goes, wherever the Gospel spreads, this same Son is already present amongst all peoples, all religions, all faiths. Christ is the Savior of all, including those who do not know Him as Jesus Christ. And here we recall the words of St Paul: “This grace was given to me to bring to the Gentiles the news of the boundless riches of Christ, and to make everyone see what is the plan of the mystery hidden for ages in God who created all things; so that through the Church the Wisdom of God in its rich variety might now be made known.”

Christ reveals what was present all along. And what was present all along is Him.

We love the Magi because they’re us, don’t we? Few Christians today claim Jewish identity. In Scripture, we are the Gentiles, the pagans, the nations gathered by God and grafted by grace into the New Israel, into the Body of Christ. The Magi hail from everywhere and nowhere. They represent all ages, all races, all continents, guided by nature and by pagan myth to the Light of the Son of God.

The early Church believed that just as God prepared the Judeans for Christ by the Law of Moses, so He prepared the Greeks by the philosophy of Socrates and Plato. Later generations took this to the next logical step: If God prepared Jews by Law and Greeks by philosophy, He then prepared the barbarians by their mythologies. Christ did not come to abolish Celtic or Norse or Classical paganism; He came to fulfill everything about them that was good. Behold, He says, I make all things new!

My point is simply this: no matter who we are, where we go, what we do, God is with us. God has always been with us. And not just God the Father unknowable beyond the heavens but also God the Son, God-With-Us, God made manifest. That’s literally what epiphany means: the manifestation of the Son of God to all.

This then is our job, dear Christians: not the threaten, not to terrify, not to tell the world to convert or die, but to reveal the love of God for all peoples of all nations, for every race and tribe and tongue, made known to us in Jesus Christ our Lord. Like the Star in the midrash, Christ is always leading us forward, out into the world, into the need of our neighbor. But just like that same Star, He is also already waiting for us at our destination, welcoming us with a different form, a different face.

In revealing the Son of God to others, He is revealed to us yet again. We are all the people of God in Jesus Christ our Lord. And sometimes, oftentimes, Christians need to be reminded of this even more than pagans do.

In the Name of the Father and of the +Son and of the Holy

Spirit. Amen.

Comments

Post a Comment