Hard Prayer

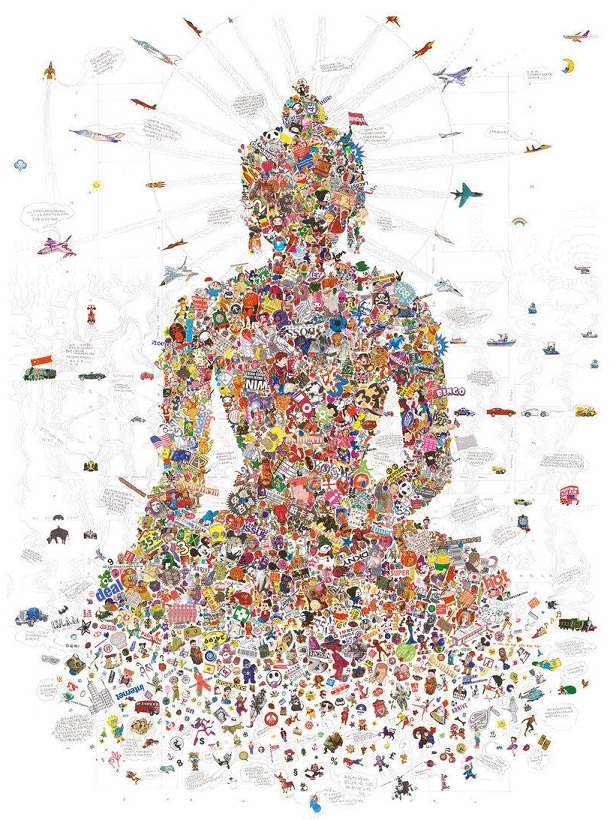

Rebel Buddha, by Dzogchen Ponlop

Lenten Vespers, Week Two: Prayer

Reading: Matthew

6:5-13

Homily:

Lord, we pray for the preacher, for You know his sins are

great.

Grace, mercy and peace to you from God our Father and from

our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ. Amen.

Prayer is the lifeblood of the Christian. When we neglect prayer,

we wither within. And there is no better time to rededicate ourselves to the life

of prayer than during the season of Lent. Along with fasting and almsgiving, it

is one of the three pillars of Lent. But I think we have a lot of

misconceptions regarding it.

Prayer, for instance, is not a magic spell. It’s not reaching

out to a God who would otherwise be ignorant of our plight. We are assured that

He already knows what we need far better than we do. Prayer is not to make

wishes, or demands, and it certainly cannot be our way of testing God, as

though He were ours to command.

What then is the point of prayer? It is nothing less than to

open ourselves to the presence of God all around us: the infinite ocean of

Being, of Love, of Goodness and Truth and Beauty. In Him we all live and move

and have our being, after all. It is in prayer that we are at our most human,

most awake, most alive. To pray is at once both the easiest thing in the world,

yet also a discipline that requires mindfulness, willpower, and determination.

It is very hard to let go and let God. Many things vie for our

attention. We are inundated with distractions, temptations, and diversions, all

stemming from the unholy trinity of the devil, the world, and the flesh; that

is, the things beyond us, around us, and within us that draw us away from our

God.

So—how then do we pray? Traditionally, Christians enter into

prayer in three ways: oration, meditation, and contemplation.

Oration is the one with which we’re most familiar. It is

simply speaking to God, be it with our inner or outer voice. In oration, we lay

our petitions before the Lord. We repent of our sins, give thanks for His

blessings, and unburden ourselves of the worries and vicissitudes of life, by

laying them upon the shoulders of Christ. We speak to God as our Lord and

Father above us, as our Brother in Christ beside us, and as the Spirit of Truth

within us.

Sometimes we pray old, familiar, beloved words: the Our Father, the Hail Mary. Sometimes we pour out whatever comes to mind, whatever vexes us, troubles us, uplifts and elates us. And these prayers are good and true, even if they seem uninspired and unworthy, even if we have to pray that God pays attention to our prayers when we ourselves do not.

Sometimes we pray old, familiar, beloved words: the Our Father, the Hail Mary. Sometimes we pour out whatever comes to mind, whatever vexes us, troubles us, uplifts and elates us. And these prayers are good and true, even if they seem uninspired and unworthy, even if we have to pray that God pays attention to our prayers when we ourselves do not.

We are promised that when we pray to God our Father, we are

praying along with God the Son, and that God the Spirit within us intercedes

through sighs too deep for words. God inspires our prayer, receives our prayer,

and prays our prayer. The simple act of speaking to our God, even silently in

our minds, is to participate in the life of God, to enter within the Holy

Trinity of Father, +Son, and Holy Spirit.

And this, I suspect, is where most Christian prayer ends. By

rights, however, this ought only to be the beginning, for beyond oration is

meditation. And this is a species of prayer from which we would all benefit. To

meditate is to focus on a story, a verse, a prayer, an image, and to delve

deeply into it, letting it soak into our bones, savoring it for the fullness of

flavor, the depths of its meaning. When we read a passage of Scripture and chew

on it, that’s meditation.

Another form of meditation is to repeat a short verse or

prayer not simply to babble but to cling to it, cling to God through it. The

prayer ropes of the East repeat the Jesus Prayer: “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of

God, have mercy on me, a sinner.” You couldn’t find a simpler prayer—“Lord,

have mercy”—yet we could never exhaust its riches. Orthodox Christians whisper

it time and again, allowing it to fill their souls, excluding all the wild and

listless thoughts of the restless modern mind.

In the West we have the Rosary, the repetition of simple prayers

in groups of 10, while an image or story from the life of Christ is held within

the mind, so that the prayers in their decades become the Gospel on a string. When

we pray the Rosary daily, we meditate on the birth, life, death, and

resurrection of Jesus all throughout the week. The story of Christ becomes part

of us deep in our bones. Meditation is prayer of another level, quieting the

mind to exalt the spirit.

And this brings us to the most neglected yet most needful form

of prayer in modern life: contemplation. Contemplative prayer is radically

countercultural, because it consists of silence and of active inaction. No

busywork, no distractions, no words. If necessary, a simple mantra, or even

just the Name “Jesus” may be held in the mind in order to keep us in the

moment, to keep us from filling our heads with noise. But contemplative prayer

is simply sitting in silence in the presence of God.

For some, that means coming into the sanctuary. For some that

means being out in nature, in the deer stand or the fishing boat. For some it

simply means going into our room and shutting the door. Silence your phone and

set a timer. No music, no radio, no background noise. Listen in the silence for

your God. If your mind starts to wander, perhaps God is leading it somewhere

important. Should it go too far astray, however, come back to the moment, come

back to Jesus.

Contemplation is both effortless—you don’t really do anything—and

quite difficult. We are petrified of silence, you and I. We want to fill it up

with entertainment and diversions and what we disingenuously call productivity. We must do less and be more. Sit in silence for five minutes a day: then 10, then 20, then 30. Simply by

being in the presence of God we defy the empty pleasures of the devil, the

world, and the flesh. We defy a society which insists that we must always be

pursuing, always be consuming. The Buddhists have never forgotten this, but we

as Christians have.

Oration. Meditation. Contemplation. We need all three of

them more than we know. And in truth they overlap, one blending into another, for

to commune with God defies easy explanation or clear definition. Prayer is

something that must be practiced and experienced in order to be understood. Lex

orandi, lex credendi: the law of prayer is the law of belief.

As Christians we are called to pray throughout the day, at regular

intervals, so that time itself is sacralized, and we enter thereby into the

rhythms of Creation. Let us then, my brothers and sisters, embrace the

discipline of prayer for these 40 days of Lent—and then, God willing, for all

the days thereafter.

In the Name of the Father and of the +Son and of the Holy

Spirit. Amen.

Comments

Post a Comment