Hero's Journey

Propers: The Fifth

Sunday after Epiphany, A.D. 2019 C

Homily:

Lord, we pray for the preacher, for You know his sins are

great.

Grace, mercy and peace to you from God our Father and from

our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ. Amen.

One of the more interesting insights to come out of the

twentieth century was the notion of the Hero’s Journey, first put forth in a

book by Joseph Campbell entitled The Hero

with a Thousand Faces. Campbell argued that many of humanity’s greatest

stories share a common underlying structure. Our myths, in other words, have

the same bones.

This might’ve remained an obscure enough idea, save for the

fact that influential film makers, such as George Lucas, used the structure of

the Hero’s Journey to create movies like Star

Wars, which has developed into a mythology all its own. Campbell went a

little too far with his idea. He thought that hidden away in the mists of

prehistory, or perhaps in the darker recesses of the human mind, there existed

an original monomyth, one great sacred story from which all other great stories

descend. This is simply not the case.

From a spiritual perspective, however, Christians might well

argue that there is one great Story to which all other great stories point.

What is the Hero’s Journey? I think the writer Dan Harmon

summarized it best when he spoke of a “story embryo” consisting of eight parts:

(1) the hero begins in a place of comfort; (2) but wants something; (3) so he

or she sets out into the unknown; (4) and adapts; (5) the hero finds what he’s

been looking for; (6) but pays a high price for it; (7) then returns home; (8) having

changed.

Campbell had a few more twists and turns thrown in there,

mentor characters and the like, but I think Harmon’s embryo really gets to the

core of the thing. Great stories follow the Hero’s Journey. And this has

influenced not just writing and filmmaking but indeed the entire field of

psychology.

Jungians such as Jordan Peterson talk about the psychological

significance of dragons guarding their treasurers within caves. In order to get

what he wants, the hero must venture out into the unknown, down into the dragon’s

lair, because it is in darkness that both danger and opportunity arise. In

order to learn, in order to grow, in order to mature as human beings—indeed, in

order to tell a good story—we must travel back and forth between order and

chaos, exploring the unknown, and then returning to our center, having changed.

So what does all this have to do with Christianity? Quite a

lot, I should say. Because of course, stories are not limited to books or films

or to the psychiatrist’s couch. Stories are how we make sense of our lives: the

stories we tell to ourselves about who we are, how we got here, and the life we

have lived to this point. Life is a story.

And stories have a narrative structure. They have a

beginning, a middle, and an end; which is to say that our lives have a goal.

They have meaning and purpose and value. Our stories follow the Hero’s Journey

because we follow the Hero’s Journey. The Hero’s Journey is life properly

lived.

And then there’s Christ, whose life is our life writ large.

God Incarnate came to earth as the perfect human being, and so He is the model

of what we were meant to be. His story is the greatest myth, because it is

true. It is written into history, in flesh and blood and bone. All of our myths

are longings for the true myth of Jesus Christ. If you don’t believe me, read

Tolkien. Read C.S. Lewis. They understood that in Christ, all of our myths are

perfected, all of our fantasies come true.

And when we encounter Christ—in the Bible, in our lives, in the

Sacred Mysteries of the Church—we can do no other but fall down on our knees in

wonder and humility. For His own perfect holiness lays our sinful selves bare. And

in this at least we are in good company. Look to our Scripture readings this

morning.

Isaiah, in response to a thunderous vision of Heaven, quails

in fear before the holiness of the Lord. “Woe is me!” he cries. “I am lost, for

I am a man of unclean lips, and I live among a people of unclean lips; yet my

eyes have seen the King, the Lord of hosts!” Isaiah does not quail because God

is so horrible. He quails because God is so good, and he knows he is not.

Likewise Paul: “I am the least of the apostles,” he writes, “unfit

to be called an apostle because I persecuted the Church of God.” And Peter, seeing

the miracles of the Messiah, falls to his knees upon the beach and cries: “Go

away from me, Lord, for I am a sinful man!”

Yet God’s response to all three of these sinners is the same:

God makes them holy. Isaiah is touched with fire taken from the altar of God

and is thus purified to prophesy the Word of the Lord to the needs of his own generation.

Paul, in the midst of his persecutions, is struck blind by a vision of Christ, and

thereby are his eyes truly opened for the very first time. And Peter the

fisherman is raised from his knees to become prince of the apostles, tasked now

with fishing for men.

God’s response to the confession of His people’s sin in all

three cases is not simply to wave His hand and say, “Forget about it,” as

though forgiveness were but the pressing of a button, the pulling of a lever. Rather,

God forgives them by giving to each a calling, a mission, sending them out to

do God’s own glorious, dangerous work in this world.

He sets them, in other words, upon the Hero’s Journey—“I

send you out as sheep amidst the wolves!”—and thereby do they grow, and thereby

do they change, and thereby are they forgiven. They are sent out literally to

fight the dragon. Thus do they find their true treasure, the pearl of great

price, and return home again to paradise, having been transformed.

Please understand what I’m saying. It’s not that Isaiah and Peter

and Paul asked for forgiveness, and God said, “Okay, but only at the end of

this long road.” Not at all. Rather the quest itself—the Hero’s Journey of

following Christ out into a fallen world—is their forgiveness. They are called

to a higher form of life.

The mission of the Christian, the calling of God’s people,

is to live out Christ’s own death and resurrection every day, and to live it

out for others: going out from comfort, wading through the chaos, paying the full

measure of the price that must be paid, and coming home again transformed. Such

is life as it is meant to be lived: fearless, selfless, deathless, dauntless.

This is what it means to be a Christian. This is what it means to be a hero.

And it may not look like anything particularly glamorous to

the world. One gains little praise in living humbly, generously, selflessly. Yet

I promise you that in the eyes of the Lord, and in the hearts of those in need,

there can be no higher calling, no greater honor, no fuller life.

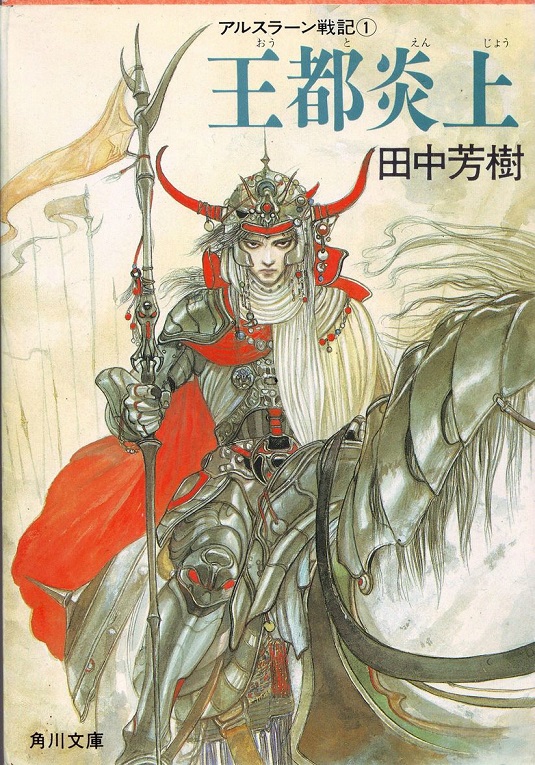

Think of this when we read the great books, when we watch

the great films, when we tell the great tales. The heroes that we love are who

we are meant to be, sent out by God to fight the dragon, to claim the treasure,

to save this fallen world. The journey itself is our mission, our calling, our

very salvation, poured out freely upon unworthy sinners for the redemption of

all and for the whole of Creation.

You may think that you’re no hero, but Christ has called and

made you so. Thus with the Church of every age, we are made bold to confess the

great mystery of the Resurrection: “I am saved; I am being saved; and I hope to

be saved.”

Every story has an end. Every journey brings us home. Fight

the dragon. Save the wicked. Win the world for Christ. For He claims us sinners

as His own, and sends us out heroic.

In the Name of the Father and of the +Son and of the Holy

Spirit. Amen.

Comments

Post a Comment