The Humor in Our Sin

Propers: The

Eleventh Sunday after Pentecost (Lectionary

18), A.D. 2018 B

Homily:

Lord, we pray for the preacher, for You know his sins are

great.

Grace, mercy and peace to you from God our Father and from

our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ. Amen.

There is a certain gallows humor in the Bible that I think

we often overlook. And in few places does this penchant for the absurd shine

through more clearly than in the story of the Israelites in the wilderness. The

Exodus is a funny book—if for no reason other than its brutal honesty regarding

just how ridiculous our behavior as human beings tends to be.

Let’s recap, shall we? The Hebrews suffer some 400 years of

oppression, forced labor, and mass infanticide. They call out to God for a

savior, whom He sends—and not just any savior, but Moses, a prince of Egypt, a

man with a foot in both worlds. And he shows up working wonders and proclaiming

release for the captives; and how does his own family respond to this answering

of their prayers? How do God’s chosen people react to God’s chosen Lawgiver? They

complain: Thanks a lot, Moses. Thanks for riling up Pharaoh. Thanks for making

everything worse!

So God works greater wonders through Moses. He calls down

plagues upon the dark gods of Egypt, revealing their impotence before the

Creator of All Worlds. He preserves His people from illness and pestilence and

famine and hail. He showers them with the silver and gold of their captors, parts

for them the Red Sea as an escape route, and leads them in a pillar of cloud by

day and a pillar of fire by night. In all of this, God lays low the greatest

superpower of the ancient world in order to liberate slaves, servants, nobodies—whom

He loves.

So now they’re out in the wilderness, being led to the

Promised Land—the land of milk and honey, the land of their ancestor Abraham—and

what do they do? They complain, again. “If only we’d died in Egypt, where at

least we had good food!” Thanks a lot for liberation, Moses. Glad we aren’t

slaves anymore, Moses. But now where are we supposed to find a decent place to

eat?

It takes a lot of nerve to watch God wipe out the chariots

of Egypt before your eyes, and then turn around and say, “Well, I’m bored. Can

we go back now?” But that’s the thing about the Hebrew Bible; it’s very

self-critiquing. No other ancient people’s record is so bluntly honest about

their own shortcomings and sins.

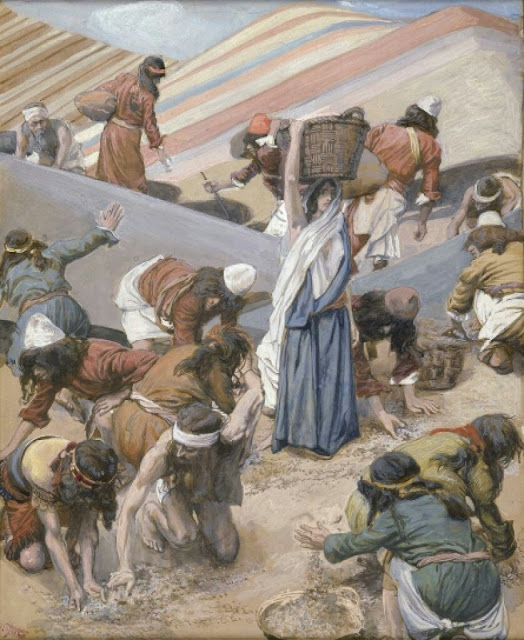

All of which brings us to this morning’s story of the manna.

The people are complaining. They’ve got their gold, their silver, their

families and their freedom, but they miss the fleshpots of Egypt—which,

incidentally, would make a great name for a band. And then suddenly they get up

one morning to find something strange covering the ground like frost. They don’t

know what it is, but it reminds them of bread, light and flaky, and tastes like

wafers made with honey, which is to say, delicious.

It’s all over the place. They can just pick it off the

ground effortlessly and eat their fill. It’s a bit like waking up to find the

world covered in cookies or gingerbread. They’ve never seen anything like this,

so they call it manna, which means “What is this?” On Fridays Moses tells them

to gather twice as much, so that on Saturdays they can observe the Sabbath

rest, not even having to bend over to gather it.

And then in the evening, believe it or not, the wind blows

in an exhausted flock of migrating quails, which collapse right in the middle

of the camp, again covering the ground like dew, like frost. And so in the

morning you have fresh, sweet bread delivered to your door—or at least to the

entrance to your tent—and in the evening fresh meat without even having to hunt

or catch the birds. The meal comes to you, and comes in abundance.

Oh, and there’s plenty to drink, too. Moses goes around by

the power of God turning bitter waters into sweet, camping where a dozen fresh

springs pop up.

It’s an image that is ridiculous. God answers their prayers,

answers their complaints, superabundantly, humorously. He did everything but

send genies to be their waiters and waitresses. And how do you suppose that

they respond? Are the people joyful, grateful? Are they abashed at their

earlier grumblings? Of course not. They complain. They always complain. For 40

years they complain.

There’s even a scene in the Exodus whereby God and Moses

sound like a pair of exasperated parents: “Look what your people are doing!”

God says to Moses. “Oh, no,” Moses replies, “those are Your people, not mine.

Don’t blame me.” There is humor here, even if it’s a gallows humor, a humor

that highlights our sin. Because we’re just like this, aren’t we? We complain

about how bad we have it, thinking that if life were just a bit better then we

might be grateful for it.

But the truth is that the more we have, and the better we

have it, the more we tend to complain. Gifts become expectations. Grace becomes

entitlement. If we are not grateful for the little that we have, then we shan’t

be grateful for a lot.

Which is not to say that we all have it easy, or that all

complaints are baseless. But many a truth hath been told in jest, and the truth

told here is that those who are ungrateful will likely remain so regardless of

our possessions or positions. And so we chuckle at the Exodus, because the

people in it are all-too-familiar, all-too-human. In them we see our own

ingratitude, our own self-delusions, our own twisted hearts. And there is grace

even in this, for we know that God understands.

Of course, the true Bread from Heaven is not manna but the

One whom manna prefigures: that is, Jesus Christ our Lord. Jesus is the Bread

of Life. Like wheat that falls to the earth and is buried—only to rise again to

feed the world—Jesus is God come down, God emptying Himself, becoming human,

becoming mortal, that the Creator might now enter into His own Creation, and thus

pour out His own immortal Life for us, for the life of our world.

In Jesus, God gives to us all that He has, all that He is.

As the ancient Fathers liked to put it, “God became man so that man might become

a god.” These days we have a pithier saying, perhaps more to the point: you are

what you eat. So then, if Jesus is our Bread of Life, Jesus our true Cup of

Salvation, and in this Meal, we, like all who have gone before us and all who

follow after, eat the Body, drink the Blood, of God incarnate on this earth—what

then does that make us?

It makes us Jesus. It makes all of us, together, the living

Temple and Bride and Body of Christ still at work in this world, still

forgiving, still healing, still and forever calling wayward sinners home. “Eat

this Bread. Drink this Cup. Come to Me and never be hungry. Eat this Bread.

Drink this Cup. Come to Me and you will not thirst.”

Brothers and sisters, I am often overcome by the worries of

this world—by boredom and stress and that uniquely American exhaustion that seems

to set in amidst the ever-growing piles of our ridiculous abundance. And caught

up in these diversions, these distractions, I find myself thinking, “What has

He done for me lately? What difference does God really make in my life today?”

Thus do I sound like Israel in the wilderness. I sound like

people surrounded by sweetbreads spread out as frost upon the ground and quails

falling straight from the skies into their stewpots, yet who still somehow find

reason to complain. “Waiter, this food is terrible—and such small portions!”

And so I have to laugh. Because here I am surrounded by the

superabundance of God’s mercy—God as my Bread, God in my Cup, God’s Spirit in

my soul, God’s Blood in my veins—and still I think, “Is this all? Is that all

You’ve got?” Ah, my dear Christians, I am such a fool. And that makes me laugh.

Gallows humor, I suppose.

Every Sunday we are given that of which the people of

ancient Israel could only dream. We are given forgiveness, resurrection,

purpose and new life. We are given God Himself poured out into us, into my own ungrateful

heart, utterly out of love, utterly out of grace. We are given a God we can see

and touch and taste and eat, a God so generous that we would fall cowering to

the earth if we even began to realize what all we are gifted in this one holy

sacred Meal.

He knows all our sins. He knows all our hearts. He knows how

stupid and silly each one of us can be. And yet He comes every Sunday, to meet

us in that Font and on this Altar, because our lives—your life—is more precious

to Him than His own.

For the bread of God is

that which comes down from Heaven and gives life to the world.

In the Name of the Father and of the +Son and of the Holy

Spirit. Amen.

Comments

Post a Comment