Fear

Scripture: The

Fifth Sunday after Pentecost (Lectionary

12), A.D. 2016 C

Homily:

Grace, mercy and peace to you from God our Father and from

our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ. Amen.

Fear. You can smell it all throughout the Gospel text this

morning. This is a story about fear.

It starts off with a small boat crossing deep water. The Sea

of Galilee is about eight miles wide and 13 miles long—not huge, mind you, but

no small jaunt either in an age before outboard motors. As Jesus dozes off, a

mighty windstorm suddenly sweeps across the surface of the water, tossing the

ship about, with high waves sloshing such volume into their craft that the

Apostles are certain they will soon be swamped and drowned.

Throughout the ancient world, and certainly in the Bible,

the sea represents death. It is the realm of chaos, of darkness, of monsters in

the deep. The people of the Bible are terrified of open water, yet when they

cry to Jesus, “Master, awake! We are perishing!” Christ seems almost nonchalant

about their plight. “Where is your faith?” He asks, and with but a word He

rebukes the wind. Suddenly the storm falls silent; suddenly the waves collapse.

And in many ways that calm is more terrifying than the fury of the sea. In

ancient mythologies, the strongest of pagan gods is always the storm god, the

thunder god. But to Jesus the storm is nothing, absolutely nothing. “Who is

this,” whisper the stricken Apostles, “Who commands even the winds and the

water, and they obey Him?”

Having passed through the rages of the storm and waters of

death, the Apostles now find themselves on the other side: amongst the tombs;

amongst the dead. In this pagan land of the Decapolis, in the city of the

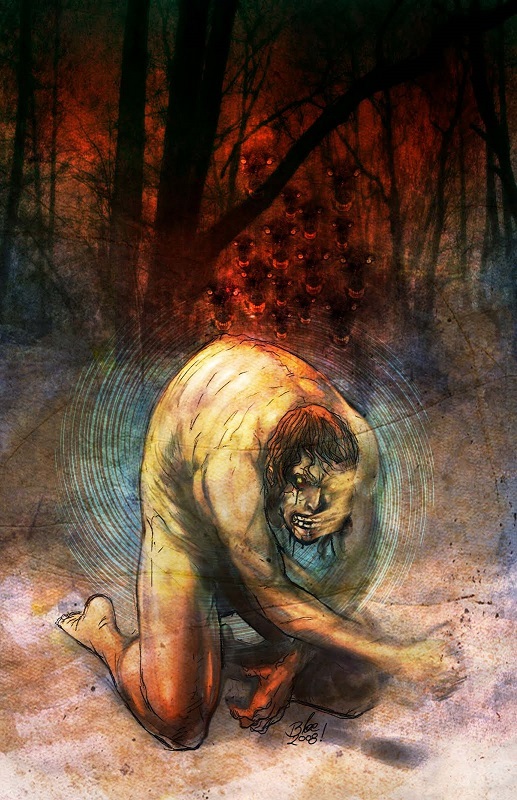

Gergesenes, a raging lunatic comes crawling out of the graveyard to meet them.

He is bound with broken chains, feral and unkempt, clothed in rags at best. He

is a wild man, a wolf-man. In biblical times, being unclothed—or at least,

improperly clad—was indicative of a living death. Slaves, prostitutes and

madmen lacked true clothing as a sign of their loss of personhood. This

unclothed fellow here lives in tombs, driven by wild voices, expelled even from

his own heathen community. How would you react if such a creature met you on

shore? I might get back in the boat!

And as if all this weren’t bad enough, the Apostles have to

face the horrific reality that the voices in this man’s head might not be of

his own generation. There are powers at work here even deeper and darker than

the subconscious human mind. This man’s head is full of demons—a possibility so

disconcerting that many today would dismiss it out of hand. Yet the ancient

world was quite familiar with demons. They didn’t understand them as fallen

angels but as infernal gods: dangerous lords of the underworld, whose unholy

pacts could unleash great power but only at great price. These things dwelt in

caves, in deserts, and here in graveyards.

Yet these demons, these unfathomably dark and ancient gods,

suddenly recoil in fear. “What have You to do with us, Jesus, Son of the Most

High God?” the devils shriek. “We beg You, do not torment us—do not cast us

back into the Abyss!” First storms, then madmen, now demons? It seems no matter

how terrifying the foe, Jesus is yet more fearful to them.

Who is this Jesus, that even the winds and seas obey Him?

Who is this Jesus, that even the black spirits of the Abyss rear back in

stammering terror? And so with but a word, this Jesus banishes an entire legion

of demons from a man who for years has shattered chains and raged savagely

amongst the tombs. When the townspeople come out to see what has occurred, they

are shocked to find their demoniac, their local madman, clothed and in his

right mind. Christ has returned to him his sanity. Christ has returned to him

his personhood. He is a man again.

And how do the townspeople react to this astonishing turn of

events? With joy and celebration? With rapture and awe? No. They respond as I’m

sure we would, were we to witness such inexplicable happenings. They react in

fear. Who can this be, this unprepossessing Jew from across the sea, that the

devils flee headlong into swine, and drown in the foam of the sea rather than

stand before His face? “Please, Jesus,” the Gergesenes ask, “please, we beg

You, just go away.” He is too much, it seems, for them to handle. Too much,

really, for any of us to handle.

Amazingly, Jesus does precisely as they ask. He gets back

into His boat along with the Apostles—who by this point must have white hair

and high blood pressure—and He returns to the Galilee. Jesus, it seems, has

come all this way, rebuking storms and banishing demons, for no other reason

than to cure this one lowly outcast man: a man who had no home, no family, and

no hope of salvation; a man who was already living amongst the dead. Yet for

this nobody, this non-person, Jesus crossed the stormy sea and faced down the

powers of hell itself, all for someone whose name God alone appears to know.

Little wonder that our former demoniac begs to return with

them to the Galilee. Oddly, this is the one request in today’s story that Jesus

denies. But notice what He does say to him, because it proves to be the point

of our entire twisted tale: “Return to your home,” Jesus says to the man, “and

declare how much God has done for you.” It is perhaps the most shocking thing

that Jesus could possibly say. Right here, at the climax of our story, Jesus

answers the question which the Apostles have been asking from the beginning. “Who

is this,” they wonder, “that even the storm and the wind, the devils and

demons, obey His command?” And now Jesus answers quite clearly: God. God has

done this. In Jesus Christ, God Himself walks upon the earth. Terrifying doesn’t

begin to describe it.

Within the hierarchy of the human soul, fear is a passion.

It tells us when to flee, and when to fight. Like fire, fear can be a good

servant but a terrible master. We cannot let our fears control us. And we

cannot allow others to control us through our fears. Here we are, modern

Americans, so rich, so powerful, so free—and yet so fearful. Afraid of getting

old. Afraid of dying alone. Afraid of watching our world come tumbling down

about our ears. Some of our fears are justified: fears of war, of violence, of

political demagoguery. Some of our fears are foolish: fears of the unknown, of

the alien, of the other. But we must not let our fears rule us. We must not let

them rage like wildfire, out of control.

We must harness our fears to steel ourselves for the hard

work of healing, defending, and forgiving; the hard work of loving our neighbor,

and welcoming the outcast, and building a community founded upon justice and mercy

and mutual love. We must be brave enough to live virtuously. We must be

courageous enough to pass on to our children the goodness and truth and beauty

bequeathed to us by our forebears. We must be bold enough to live in such a way

that we will not allow violence and fear and prejudice to divide us, to cut us

off from the love of God found only in loving our fellow human beings.

Every day we hear of wars and rumors of war. Every day we

read of senseless killings, of fatherless 20-somethings lashing out in anger with

their society’s rifle of choice—the AK in the East, the AR in the West—at groups

they blame for their own hopelessness and anomie. And yeah, it’s scary. And

yeah, we need to act. But not in fear. We cannot respond to hatred with

ignorance and anger. We cannot demonize our opponents as if they were some

species separate from our own. Christians have always been called to a third

path, a way between violence and surrender; a strong and active love that

embraces faith and reason, outreach and defense; a path that fights darkness

with light, hatred with forgiveness, and death with everlasting, superabundant

life.

We are not just called to stand against unjust death. No, ours

is a charter more scandalous than that. We are called to stand against all

death, everywhere, against the grave itself!—to proclaim the Good News that

Jesus is Risen and we shall arise! Hallelujah!

Ours is a world filled with storms and devils. We find

ourselves cast out upon deep waters, or living already amongst the tombs. But

no one who has seen the face of Christ can ever seriously fear madmen or chaos

or even death itself. God walks upon this earth, wonderful and terrible and

mysterious and inscrutable and unstoppable and all-loving. He is more

terrifying than our terrors, more monstrous than our monsters, and He will walk

upon waters and stultify storms and damn all the devils to meet us in our

madness, to free us from our fetters, to raise us up from our living death

amongst the tombs and send us out to “Go! Go and declare what God has done for

you!”

God is stronger than fear, stronger than hatred, stronger

than death itself. Remember that, when evil seems ascendant and terror gnaws

our bones. Remember that Christ has died, Christ is Risen, and Christ will come

again. Remember that He is on the march even now, and His victory is assured. Remember

this, and rule your fear. For the very things that we are afraid of, the things

that cause us to quail, are themselves utterly terrified of the face of God made

visible in Christ Jesus. And if He is for us, brothers and sisters—then there

is nothing in this world to fear.

In the Name of the Father and of the +Son and of the Holy

Spirit. Amen.

Comments

Post a Comment