God of Slaves

Lenten Vespers, Week Four

Exodus 21: Free the Slave

When you buy a male

Hebrew slave, he shall serve six years, but in the seventh he shall go out a

free person, without debt. If

he comes in single, he shall go out single; if he comes in married, then his

wife shall go out with him.

Deuteronomy 5: You Were Slaves

Remember that you were

a slave in the land of Egypt, and the Lord your God brought you out from

there with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm.

Matthew 5: Love Your Enemy

You have heard that it

was said, “An eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth.” But I say to you,

Do not resist an evildoer. But if anyone strikes you on the right cheek, turn

the other also; and if anyone wants to sue you and take your coat, give

your cloak as well; and if anyone forces you to go one mile, go also the

second mile. Give to everyone who begs from you, and do not refuse anyone

who wants to borrow from you. You

have heard that it was said, “You shall love your neighbor and hate your

enemy.” But I say to you, Love your enemies and pray for those who

persecute you, so that you may be children of your Father in heaven; for

he makes his sun rise on the evil and on the good, and sends rain on the

righteous and on the unrighteous. For if you love those who love you, what

reward do you have? Do not even the tax-collectors do the same? And if you

greet only your brothers and sisters, what more are you doing than others?

Do not even the Gentiles do the same? Be perfect, therefore, as your

heavenly Father is perfect.

Homily:

Grace, mercy and peace to you from God our Father and from

our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ. AMEN.

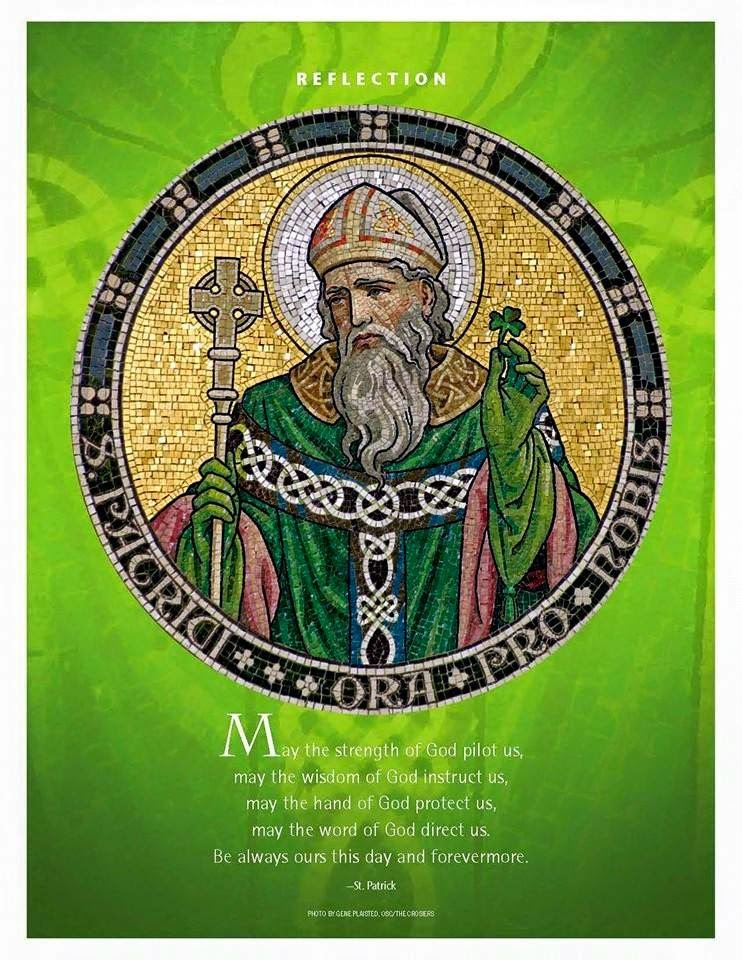

St. Patrick was Welsh, not Irish. And, as we are often

reminded, St. Patrick’s Day isn’t even all that big a deal in Ireland. Then

again, the Irish-American population is seven times the size of Ireland’s own,

so perhaps they might consider following our lead on this one.

St. Patrick’s Day came to be celebrated in America first as

a political movement, then as an ethnic festival, and finally as yet another

drunken bacchanal. More’s the pity, given how wonderful the story of St.

Patrick truly is. In previous years I’ve preached upon both his writings and

his miracles, but this time around I think we ought to address the elephant in

the room: slavery.

St. Patrick was a slave. He began life as a wealthy young

man, a Romanized Celt living in Britannia. The name Patrick, after all, derives

from “patrician.” He was seized in his youth by Irish pirates who sold him into

slavery to a man named Miliuc. After six years of suffering—mostly spent in lonely

isolation and exposure to the elements as he shepherded Miliuc’s sheep—Patrick received

a vision from God leading him to freedom. After a truly miraculous journey both

by land and by sea, Patrick escaped to Europe, was reunited with his family,

and became a priest.

Then came a second vision: that of an Irishman crying out

for Patrick’s help. And so Patrick returned to the Isle of his enslavement in

order to preach a Gospel of forgiveness, mercy, and liberation to the very

people who had torn from him his youth. He met with great resistance, but also

with great success. And ever his concern was for the poorest and lowliest of

all: his fellow slaves. I find it particularly significant that Patrick is said

to have converted a certain Pictish slave to Christ, a woman who would later

give birth to St. Brigid—arguably the only Irish saint more influential and

beloved than Patrick himself.

Christianity flourished in Ireland, not by the sword but by

the Word of God. Pagan druids eagerly became Christian monks and nuns. The dark

gods were driven out, as we commemorate in the legend of Patrick casting out

the snakes. When the Dark Ages fell upon the Continent, Ireland kept the light

of the Gospel, and of education more generally, burning brightly for the world

to see. Irish missionaries brought Christ to the kings and queens of Europe,

who had largely been baptized without knowing what all Christian baptism

entails. Thus from the chaos of collapse rose the glories of the High Middle

Ages of the West.

All of this—the salvation of our very civilization—because one

slave went free, and returned to show love and compassion to his former

masters. We should all be humbled by this. We should all be thankful for this.

We should all take a lesson from this, from the mysterious workings of the God

Who loves slaves.

Slavery is a very thorny issue in the Bible. On the one

hand, slavery seems, at least on paper, to be accepted in both the Old and New

Testaments. People, we read, may be bought and sold. Yet is this not in direct

contradiction to the underlying spirit of the Ten Commandments, which rail

against treating people as if they were things and loving things as if they

were people? Does slavery not fly in the face of the Exodus, the foundational

story of God’s own people, who were slaves of Egypt, the mightiest nation the

world had yet known? The entire story of the Bible is one of God liberating the

enslaved: those in bondage to masters, in bondage to nations, in bondage to

sin, in bondage to death.

Slavery, believe it or not, began as a form of mercy. When

one ancient army defeated another, enemy soldiers could be protected, conserved—conservare in Latin, from which we get

the word “servant.” Better to take them in than to kill them all. Biblical

slavery forbids the mistreating of servants, physically, sexually, or

otherwise. Slaves are to have their families cared for, and are to have the

same standard of living as their master. God mandates rest for the slave, and,

crucially, that slaves be manumitted every seventh year, without debt and

financially secure. Slaves in the Bible may also own their own property and buy

their own freedom. So, not a great system, but certainly better than slavery as

it developed in the Americas.

Slavery has existed in every society on earth throughout the

wide span of history. Before industrialization, manpower was of immense value.

Yet the only movements to abolish slavery have come from the Bible: from

Christians and from Jews. Yes, the Bible has been used to justify owning other

human beings. But it has also proven the only basis for liberating them. It was

Judeo-Christian principle that produced the Enlightenment’s Rights of Man. It

was British evangelists who ended the international slave trade. It was New

England Protestants who burned with abolitionist furor before and during the

Civil War. Was not the Kingdom of Judah, they reminded us, destroyed by God for

their refusal to manumit their poor slaves?

It cannot be doubted that God’s will is for all men to be

free. Yet it cannot be denied that it took us a very long time to come to this

conclusion, and fully to enact it. Would it not be better, we wonder, for God

simply to unveil the entirety of His plans for us right up front, to be clear

and forceful in His will? Surely that’s how we would act, were we God. Of

course, Moses tried that very tact with Pharaoh, to no avail.

But God is patient and merciful, slow to anger and abounding

in steadfast love. His plans unfold over eons; His promises are steadfast

across generations. Oftentimes we wonder why God waits so long to act, when He

wonders the same about us. The Bible takes the world as it is, not imposing

external authority but revealing the hidden and underlying meaning already

present, if obscured, within a fallen Creation. Truth must be revealed, not

imposed. It takes time to coax barbarians into civilization. It takes time to

prepare a violent world for a Prince of Peace, Who is willing to die—even die

on a Cross—merely for slaves. And, bafflingly, for the slave owners as well.

On this commemoration of all that Christ has done through

the life and ministry of St. Patrick, let us remember the poor, the oppressed,

the victimized; those people who are treated as things, treated as property,

treated as subhuman. Remember that we were all slaves once—slaves to Egypt,

slaves to our egos, slaves to sin and death and hell—and the Lord our God

brought us out with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm, shattering those who

would stand as our fetters.

The God Who cares for slaves will not forget His people, and

He will come to set them free. On that day may we be counted with those through

whom God works to bring the liberation of the Gospel—to Israel, to Ireland, and

to all the peoples of the world.

In the Name of the Father and of the +Son and of the Holy

Spirit. Amen.

Sjoestedt's "Celtic Gods and Heroes" and Elis' "The Celts: A History" document how the Irish conversion to Christianity came not just from the slaves below but from the druids above. The traditional priests of Ireland were eager for new learning and a new God. Joyce's "Celtic Christianity" reminds us that the Catholicism willingly adopted and adapted by the Irish could help us to revitalize our spirituality today.

ReplyDelete