Hope Sucks

Scripture:

The First

Sunday of Christmas, A.D. 2014 B

Sermon:

In the Name of the Father and of the

+Son and of the Holy Spirit. AMEN.

A gentleman recently explained to me

the meaning of Christmas as

he saw it. It’s all about hope, he said.

For thousands of years before the

birth of Jesus in Bethlehem, cultures around the world had been celebrating the

winter solstice. They would gather together as families, as communities, to

drink and laugh and carouse on the darkest night of the year. This, he said,

was because they knew that many people might well die during the course of the

coming winter. Cold temperatures, harsh storms, and limited food supplies all

reminded our ancestors of just how brief and fragile life could be. The old and

the sick might not last to see the spring. And if the winter proved especially

harsh, no one might make it long enough to feel the sun’s warmth again.

And so in the face of all this,

humanity would dance. We would sing and feast and give frivolous gifts for no other

reason than to make each other happy. We were the heroic underdogs, he told me,

because we had hope in a hopeless time. We tend to forget just how recent these

hardships were. Only two or three generations back, winter was more than a mild

inconvenience. We were completely at the mercy of a cold and unforgiving

environment. But the point of Christmas, he continued, is not to remember how

harsh and delicate life used to be. The point of Christmas, he insisted, was to

remember that life is still brief and fragile today.

We all half-joke about tolerating the

holidays with our extended families, people whom we rarely see and with whom we

often have little in common. It can seem so arbitrary, getting free toys as a

child, and as an adult trying to remember the name of your cousin’s new wife as

you make awkward conversation. But the truth is that this might well be the

last time that we see these people’s faces. That part of winter hasn’t changed.

We gather on Christmas with laughing children who won’t be children for long, and

with proud grandparents who may not be around for much longer. It’s all as

tenuous, he said, as a snowflake on a dog’s nose.

It doesn’t occur to us “that there

will never be another Christmas exactly like this one, that time will move on

and people will change, and that someday your most treasured memories will be things

that, at the time you experienced them, were nothing more than detached, mild

annoyances.” That was his argument. That was the meaning of Christmas for him. “You

don’t get many of these,” he said. “Make them count.”

And he’s right. Christmas is a time

to cherish life, family, and the simple joys of hearth and home. Christmas is a

time to make merry the bleakest nights of the year. But his argument was that

the meaning of Christmas is hope in the face of hopelessness. He found humanity

heroic because we are hopeful even when we have no reason to be. My problem

with his argument is simply this: Since when has hope been a good thing?

Hope is a recipe for disaster. As a

child, you hope beyond hope that your crush will love you as you love her. And

when she doesn’t, you learn why it’s called a crush. As an adult, you can hope

for a promotion, hope for a cure, hope for a better tomorrow. But when it doesn’t

come, what has your hope given you but a farther height from which to fall?

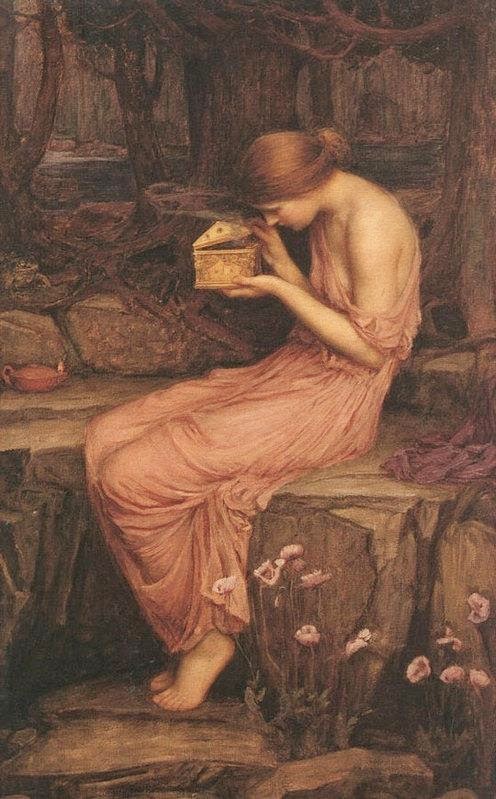

Baseless hope is a fool’s errand. The

ancients knew this. Think back to the story of Pandora’s Box. Pandora, a sort

of Greek equivalent to Adam’s Eve, cannot help but peek into a box containing

all of humanity’s ailments and woes. And as soon as that lid is open but a

crack, out rush all the world’s calamities forever to afflict mankind. But what

is left in the box? What remains to comfort Pandora in her distress? Why,

nothing other than hope. Pandora still has hope. Yet when we hear this story

with our modern ears, we never stop to think about why hope, of all things,

would’ve been stuck in the box with all the horrors ever conceived. It’s

because the Greeks saw hope itself as a woe, as a calamity, as an affliction

upon mankind. Hope, the Greeks taught, will only hurt you.

You can’t just have hope. You have to

have hope in something. If you just “hope,” we have terms for that: foolish, deluded,

naïve. And you have to place your hope not just in something real but in

something reliable. If you place your hope in a charlatan, or in a universe

that doesn't care about you, you’re still just a dancing fool. Hope by itself

is not laudable; it’s delusional.

Then again—maybe the universe isn’t

uncaring or cruel. Maybe the universe was created good, created for you. And if

so, then maybe there is something or someone higher, someone holy, who will

fulfill our ancient hopes in real and trustworthy ways, even if we don’t yet

know who or how. Then, maybe, our old pagan hopes might prove true. Then,

maybe, our hopes might find the fulfilment for which all men have longed. This,

my friends, is what shepherds found in Bethlehem one cold winter’s night. This

is what wise men sought out to worship and adore.

Only in Christianity is hope

considered a virtue. Only in Christianity do we dare to imagine that hope is a

good thing. And the only reason that we can do this, that we can be so brave

and so foolish as to set our hearts upon hope, is because we know that our hope

is not in vain. We know that all our hopes are fulfilled. “If for this life

only we have hoped in Christ,” wrote St. Paul, “we are to be pitied above all

men. But in fact Christ has been raised from the dead.” And all our hopes are

all fulfilled in Him.

That’s why Jesus remains the reason

for the season. Yes, people had hope before the birth of Jesus Christ: hope that

life might prevail over death; hope that tomorrow might be a little better than

yesterday; hope that all of our struggles and trials might mean something,

might have some eternal significance, might not be forgotten and wasted,

spilled out upon barren snows. If Jesus had not come—if God had not entered our

world and shown us that our hopes are not in vain, that life really does mean

something, that there is a purpose and an end and a love behind the great mystery

of it all—then our ancient hopes would all be for naught. It would all be just one

big, bad joke.

But He has come. Just as He promised He would! And He has brought with Him

assurance and forgiveness and a new, eternal life. He has come into this world

as the Way that never falters, the Truth that never fails, the Life that never

dies. Yes, Christmas is about hope, but not a baseless hope, not a foolish

hope. Christmas is about the sure and perfect hope that God is Love, the world

is good, and Man has a destiny far beyond the grave.

The philosopher Seneca once wrote, “Without

gods and goddesses in the heavens, the soul is not able to be sane.” That’s why

there’s always religion, always gods. We have to put our hope in something

higher, because we aren’t perfect and neither are any of the people we know or love

or on whom we rely. So we put our hope in divinity, in something that is perfect.

The only question is, will that hope be in vain?

Think of the prophets Simeon and Anna

in our Gospel reading this morning. They were promised that they would see the

Messiah of God’s people, the Savior of the world, before they died. And so they

spent their lives in the Temple, waiting, hoping, praying for that promise to

be fulfilled. We view them as heroic because they were faithful, because they

trusted in the promise of God. Yet what if Christ had not come? What if they

had spent their entire lives waiting to see the Messiah, only to die in disappointment

and despair? What if Christmas really were about a hope that never bore any

fruit? What a tragedy that would have been, all their hopes, their very lives,

brought to naught.

But Christmas, brothers and sisters,

is not about hope for hope’s sake. Christmas is about all of our hopes

fulfilled. Because Christ has come, because the hopes of Simeon and Anna came

to fruition, we can sing now with them, and with hopeful men and women of every

time and place, the joyful song that only Christmas brings: “Lord, now you let

your servant go in peace. Your Word has been fulfilled. My own eyes have seen

the salvation which you have prepared in the sight of every people: a Light to

reveal you to the nations, and the glory of your people Israel.”

Merry Christmas.

In the Name of the Father and of the

+Son and of the Holy Spirit. AMEN.

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

I've not found a contemporary textual support for the idea that the Greeks regarded Hope as a curse. Hesiod puts hope in the jar with all the curses that fly out, but to say that therefore hope is also a curse is flimsy. Were hope a curse, it should have scattered with all the others, no? A more natural reading is that hope is a mitigator, delivered with the curse because it was not needed before.

ReplyDeleteThe actual curse, of course, is the woman herself. Plato ascribes all civil strife to ambitious females (On tyranny: "It begins with his mother...")

That's just what Hope WANTS you to think. Don't trust her! She is the sister of Thanatos and daughter of Nyx!

DeleteI dunno, man. She's in a jar of toil and suffering; I was always taught that that was significant. It took St. Paul to make her a Virtue. Even Wikipedia calls her "an extension of suffering," and we can't argue with the Oracle, can we?

The whole thing makes me think of Kleobis and Biton for some reason.